The psyched out reopening of a museum

By Caroline Canault.

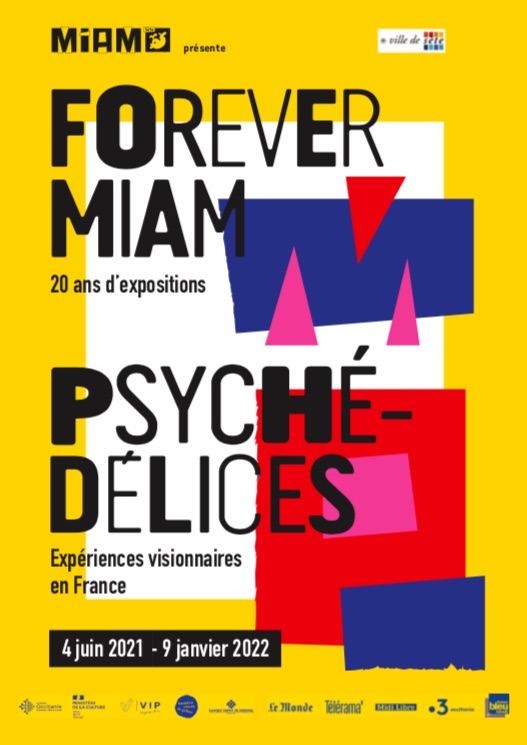

With Psychédélices, the Musée International des Arts Modestes de Sète (Sète International Museum of Modest Art, or Miam, Southern France) could not have chosen a better way to encourage the public to come and experience the pleasure of a visit to the museum once more. As crazy as it is well thought through, this exhibition perfectly crowns 20 years of curation at the helm of visionary experiences.

A little renovation work was of course needed to bring a gorgeous artistic sheen back to the MIAM, and what better time for this than our era of forced cultural restriction. This innovative museum, often showcasing work situated in the margins of creation, has, since June 4th, 2021, reopened its doors to the public in an exemplary manner, but also in the off-beat way that habitually characterises it.

The joyful exhibition, fun loving and accessible to all, presents works influenced by the illicit substances which emerged in the 70s, substances which participated in the artists’ hallucinogenic visions. Other crazed creations, issued from an imagination not under the influence, also remain just as potent when it comes to the psychedelic movement. (*)

With Psychédélices, curators Barnabé Mons and Pascal Saumadehave brought together a melting pot of young, confirmed and even hugely famous artists. The wacky yet meaningful work of local artists Cosentino, Périmon and Cervera, Combas, rubs shoulders with that of Henri Michaux, François Lagarde, Jacques Pyon, Joseph Sima and also Hervé Di Rosa (cofounder of MIAM.)

On the top floor, Belluc’s objects (Bernard Belluc is another MIAM cofounder), sourced here and there, are presented within patchworked thematic store windows making up the museum’s permanent collection. They are a fantastic conclusion of a visit to an institution that celebrates its 20th birthday this year.

(*) The movement that reveals the soul. The term psychedelic appeared in 1957 following an epistolary exchange between writer Aldous Huxley and psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond, it means “revealing the soul.” In the mid-60s, psychedelic art found a huge echo in music but much less in the pictural field as it was essentially expressed on supports which were not so much academic as linked to entertainment such as record sleeves, comics or manufactured posters. The movement remained underground with low visibility within art institutions, and progressively petered out in the 80s. The recent renewal of interest in psychedelic substances spearheaded by scientific research in the USA and Europe, along with the decriminalisation of the use of magic mushrooms in certain States of the US, are as many signs which could bring a new lease of life to this movement which now has its legitimate place in art history.