Pieces of heritage.

By Caroline Canault.

Our era has witnessed an upheaval of bodily archetypes in art. Initiated in the last century, this approach no longer aims to reproduce organic reality, but instead, to offer an account of bodies cut into pieces, stripped, torn apart, broken, then reassembled and transformed. This process stems from a technique which managed to emerge through works which have become a reference in art history. In their era, these works knew how to interpret reality in a novel fashion and question our gaze. They are still as relevant today.

In front of La preuve éternelle by Magritte (1930) or Bellemer’s La poupée (1935) the feeling of flight remains intact; the body has freed itself, graphically. Images are opposed, condensed, then reconnected, renewing internal parts with external ones, to confer meaning. This collage of a new kind increases points of view and reviews several facets of an identity we therefore see multiplied. The techniques of fragmentation and super-imposition allow the capture of a multitude of attitudes. The amplification of diversity and inequality therefore no longer censures a body which has become a figure freed from taboo.

Fifty years later, the representation of the body is once again picked apart and opened up for debate : David Hockney uses the same weapons with his assemblage of photography made up of polaroid shots. The Joiners, these mosaics of composite imagery, reconstitute portraits such as that of his mother, painted in Yorkshire in 1982. This time round, fractioned bodies push back the field of possibilities towards new aesthetic realms no longer hemmed in by a frame. “Photography helped me realise that we are only limited by the sky and our feet, never from the side.” *

HOCKNEY David (né en 1937), Mother 1, Yorkshire moors, 1985, collage photographique, propriété de l’artiste.

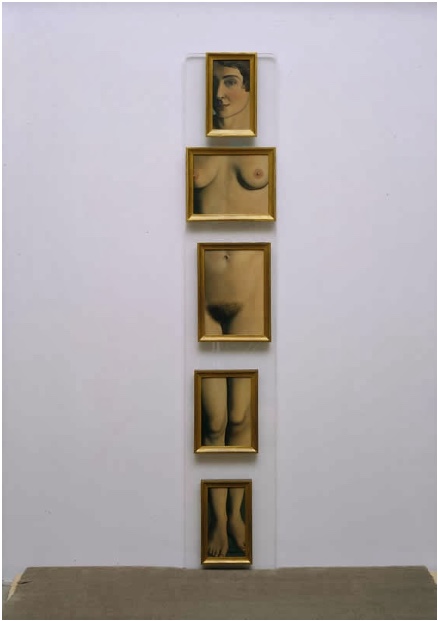

Exploiting what lies beyond the border is not the only way of achieving this. John Coplans does not hesitate to call upon the potential of the flesh whilst also reworking the frame, between 1982 and 1988, with photographs of his self-portraits cut up into pieces. Captured frontally, the artist’s body is also a space for distortion. According to this artist, he is undertaking: “an archelogy of sorts that can transcend time and go back to the origins of humanity.”**

Actually, all these examples focus on the capture and concentration of a moment without contextualizing it, or referring to the mood and state of an era. This focus is intentional – an action suspended, a cross-section analysis which could have taken place at various points in space and time. This raises the question of our bearings. It may be this point which distinguishes the works of yesterday from contemporary creation.

COPLANS John (1920-2003), Selfportrait Upside Down, 1992, deux épreuves gélatino-argentique encadrées, 44,5×28 cm, Collection privée.

Actually, all these examples focus on the capture and concentration of a moment without contextualizing it, or referring to the mood and state of an era. This focus is intentional – an action suspended, a cross-section analysis which could have taken place at various points in space and time. This raises the question of our bearings. It may be this point which distinguishes the works of yesterday from contemporary creation.

Today, conjuring up the destructured, cut up body acts as a metaphor for our current struggles and fears, social problems linked to personal growth, introspection, insecurity and instability. It raises awareness of present-day issues and works on the apparition of traces we can remember.

Finally, what is perceived differently is not so much the support and the work in itself, but rather the way in which it is interpreted. From now on, our gaze fragments the body through swipes, clicks, likes, scrolls and so on. This is a new series of gestures, a practice which has been naturally assimilated, which has almost become innate.

This is not a matter of admitting that our 21st century artists have not invented anything but of stating that all creation is cyclically regenerated, a continuity. This time, the message conveyed has societal value and contains a certain dramatic tension. We must not forget that it is read, decoded and interpreted in a singular fashion, with new tools connected to the screen.

Les us simply try not to forget the remaining traces of a past which continues to inspire our current artists, consciously or sub-consciously.

* Interview with David Hockney by Partick Mauriès published in the newspaper Libération, 9th August 1982.

** Stuart Morgan, Frances Morris- Rites of Passage: Art for the End of the Century, Tate Gallery, London, 1995