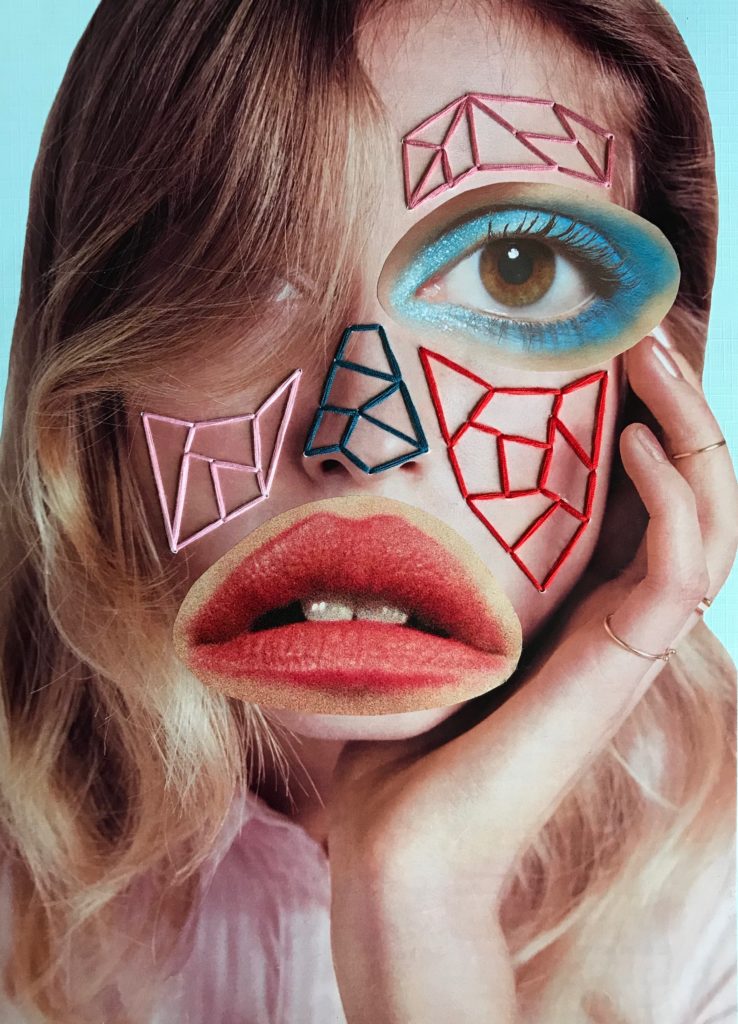

Even freaks are beautiful!

by Nadja M

“Freak’s parade” series, a tribute to the film “La Strada” by Federico Fellini.

Visual artist and participant in the DF ART PROJECT, Nadja M shares her vision of the freakish through the subjects she is currently researching, and as an aside, through the Cindy Sherman retrospective housed by the Louis Vuitton foundation due to open on 23.09.2020, an event which has been postponed because of the current health crisis.

For my “Beast & beauty” series, I felt the pressing need to distort reality in order to get a better grasp of it myself. My world is therefore populated with deformed figures, an army of monsters elaborated from bark, dried flowers, and lambswool.

The freakish has always fascinated me without my really understanding why. I probably have a special kind of attraction towards all that is different, out of bounds, even distorted. When something is deformed, this presupposes a pre-existing form, and therefore a norm. This also transgresses our usual categories, yet the border between the normal and the abnormal has never ceased to shift through the centuries.

Etymologically, monstrum conjures up the exposure of a striking and unusual phenomenon; revealing what we wanted to hide, the monster, the one we often point the finger at, and this leaves us speechless – this “monstration” comes to disturb our connection to so-called humanity.

It also crystallizes our collective anxieties, like an outlet, for our greatest joy, as our human nature, complex and ambivalent, loves to scare itself.

Contemporary American artist Cindy Sherman illustrates this perfectly. Through her photography where she is the only model, she appears in a new “disguise” (in the sense that she adopts a new guise, leaving her original appearance behind). She represents herself in portraits that are rarely flattering. Whether this applies to the “Fairy tales” series where she does not hesitate in using prosthetics (snout, teeth, breasts) or the “Clowns” one where she brings together a carnival of outrageously made-up characters, Cindy Sherman seems to derive a lot of pleasure from inventing hybrid figures, like a playful kid, figures which are half-man, half-woman.

The pleasure of transgression, the wish to inspire dislike, to turn codes on their heads by shedding light on the ugly instead of the beautiful, is, to my eyes and without a doubt, the central subject of her amazing work. She defies us with an eerie strangeness akin to that which populates the Brothers Grimm fairy tales.